Who Is Herot In Beowulf

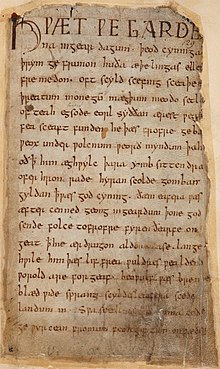

The first page of the Beowulf manuscript

Heorot (Old English language 'hart, stag') is a mead-hall and major betoken of focus in the Anglo-Saxon verse form Beowulf. The hall serves equally a seat of rule for King Hrothgar, a legendary Danish king. After the monster Grendel slaughters the inhabitants of the hall, the Geatish hero Beowulf defends the royal hall earlier afterwards defeating him. After Grendel's female parent attacks the inhabitants of the hall, and she as well is subsequently defeated past Beowulf.

Name [edit]

The name Heorot is the Old English give-and-take for a stag.[1] Its use may stem from an association between royalty and stags in Germanic paganism. Archaeologists have unearthed a diversity of Anglo-Saxon finds associating stags with royalty. For instance, a sceptre or whetstone discovered in mound I of the Anglo-Saxon burial site Sutton Hoo prominently features a standing stag at its summit.[2]

In a wider Germanic context, stags appear associated with royalty with some frequency. For example, in Norse mythology—the mythology of the closely related North Germanic peoples—the purple god Freyr (Onetime Norse: "Lord") wields an antler as a weapon. An alternative name for Freyr is Ing, and the Anglo-Saxons were closely associated with this deity in a variety of contexts (they are, for example, counted among the Ingvaeones, a Latinized Proto-Germanic term meaning "friends of Ing", in Roman senator Tacitus'south beginning century CE Germania and, in Beowulf, the term ingwine, Sometime English for "friend of Ing", is repeatedly invoked in association with Hrothgar, ruler of Heorot).[iii]

According to historian William Chaney:

Any the association with the stag or hart with fertility and the new year, with Frey, with dedicated deaths, or with archaic animal-gods cannot now exist adamant with whatsoever certainty. What is sure, however, is that the two stags most prominent from Anglo-Saxon times are both connected with kings, the emblem surmounting the unique 'standard' in the royal cenotaph of Sutton Hoo and the peachy hall of Heorot in Beowulf.[iv]

Description [edit]

Map of the Beowulf region, showing the protagonist's voyage to Heorot

The bearding author of Beowulf praises Heorot as large plenty to allow Hrothgar to present Beowulf with a gift of eight horses, each with gold-plate headgear.[v] Information technology functions both equally a seat of government and as a residence for the king's thanes (warriors). Heorot symbolizes human civilization and culture, as well every bit the might of the Danish kings—essentially, all the proficient things in the globe of Beowulf.[6] Its brightness, warmth, and joy contrasts with the darkness of the swamp waters inhabited past Grendel.[7]

Location [edit]

Harty, Kent [edit]

Though Heorot is widely considered a literary structure, a theory proposed in 1998 by the archaeologist Paul Wilkinson has suggested that it was based on a hall at Harty on the Isle of Sheppey, which would have been familiar to the bearding Anglo-Saxon author; Harty was indeed named Heorot in Saxon times. He suggests that the steep shining sea-cliffs of Beowulf would friction match the pale cliffs of Sheerness on that island, its name meaning "bright headland". An inlet near Harty is named "Country's End", similar Beowulf's landing-place on the fashion to Heorot. The sea-journey from the Rhine to Kent could have the day and a one-half mentioned in the verse form. The route to Heorot is described as a straet, a Roman Road, of which in that location are none in Scandinavia, but one leads across the Isle of Harty to a Roman settlement, maybe a villa. The toponymist Margaret Gelling observed that the description in Beowulf of Heorot equally having a fagne flor, a shining or coloured floor, could "denote the paved or tessellated floor of a Roman building". Finally, the surrounding area was named Schrawynghop in the Heart Ages, schrawa meaning "demons" and hop meaning "state enclosed past marshes", suggestive of Grendel's lonely fens in the verse form.[8] [nine] The archaeologist Paul Budden acknowledged "the story appealed" to him every bit a Kentish homo, merely felt that (as Wilkinson conceded) the discipline was "mythology, not archaeology or science".[ten]

Lejre, Zealand [edit]

A reconstructed Viking Age longhouse (28.5 metres long) in Fyrkat.

An alternative theory sees Heorot as the accurate, just Anglicised, iteration of a historic hall in the village of Lejre, near Roskilde.[11] Though Heorot does not appear in Scandinavian sources, King Hroðulf's (Hrólfr Kraki) hall is mentioned in Hrólf Kraki's saga as Hleiðargarðr, and located in Lejre. The medieval chroniclers Saxo Grammaticus and Sven Aggesen already suggested that Lejre was the chief residence of the Skjöldung association (called "Scylding" in the poem). The remains of a Viking hall complex was uncovered southwest of Lejre in 1986–1988 by Tom Christensen of the Roskilde Museum. Wood from the foundation was radiocarbon-dated to nearly 880. It was later constitute that this hall was built over an older hall which has been dated to 680. In 2004–2005, Christensen excavated a tertiary hall located just n of the other two. This hall was built in the mid-6th century, all three halls were about fifty meters long.[seven]

Fred C. Robinson is also attracted to this identification: "Hrothgar (and after Hrothulf) ruled from a royal settlement whose present location can with off-white confidence be fixed as the modern Danish hamlet of Leire, the bodily location of Heorot."[12] The office of Lejre in Beowulf is discussed past John Niles and Marijane Osborn in their 2007 Beowulf and Lejre.[13]

Modern pop civilisation [edit]

J. R. R. Tolkien, who compared Heorot to Camelot for its mix of legendary and historical associations,[xiv] used it as the ground for the Golden Hall of Male monarch Théoden, Meduseld, in the land of Rohan.[15]

The Legacy of Heorot is a science fiction novel by American writers Larry Niven, Jerry Pournelle, and Steven Barnes, kickoff published in 1987.[xvi]

"Heorot" is a brusque story in The Dresden Files ' short story collection Side Jobs.

Come across also [edit]

- Eikþyrnir, the stag that stands atop Odin'southward afterlife hall Valhalla in Norse myth

- Dáinn, Dvalinn, Duneyrr and Duraþrór, the stags that chew on the cosmological tree Yggdrasil in Norse myth

- Freyr, a Germanic deity who wields an antler as a weapon and whose proper name means 'lord'

- Valhalla, the afterlife hall of Odin in Norse myth, featuring a stag at its top

Notes and citations [edit]

- ^ "Former English Translator". oldenglishtranslator.co.britain/.

- ^ For full general give-and-take, see Fulk, Bjork, & Niles (2008:119–120). For images and details regarding the sceptre or whetstone, see the British Museum's collection entry for the object hither.

- ^ Meet give-and-take in, for example, Chaney (1999 [1970]:130–132).

- ^ Chaney (1999 [1970]:132).

- ^ Beowulf, lines 1035–37

- ^ Halverson, John (December 1969). "The World of Beowulf". ELH. 36 (4): 593–608. JSTOR 2872097.

- ^ a b Niles, John D., "Beowulf's Neat Hall", History Today, October 2006, 56 (ten), pp. 40–44

- ^ Hammond, Norman (7 December 1998). "How Beowulf's lair was pinned down to the Thames Estuary". The Times.

- ^ Wilkinson, Paul (2017). Beowulf - On the Island of Harty in Kent. Kent Archaeological Field School. ASIN B07Q27K3XG.

- ^ Budden, Gary (2017). "Background reading: Beowulf in Kent by Dr Paul Wilkinson" (PDF). Kent Archaeological Field School Newsletter (16 (Christmas 2017)): 22–23. Retrieved ix Dec 2020.

- ^ Lapidge, Michael; Godden, Malcolm (1991). The Cambridge companion to Old English literature. Cambridge Academy Press. p. 144. ISBN978-0-521-37794-ii . Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ Robinson, Fred C. (1984). "Didactics the Backgrounds: History, Religion, Culture". In Jess B. Bessinger, Jr. and Robert F. Yeager (ed.). Approaches to Teaching Beowulf. New York: MLA. p. 109.

- ^ Niles, John; Osborn, Marijane (2007). Beowulf and Lejre. Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies. ISBN978-0-86698-368-six.

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R., Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary (2015), p. 153.

- ^ Shippey, Tom, J. R. R. Tolkien: Author of the Century (2001), p. 99.

- ^ Dryden, Mary (2 August 1987). "The Legacy of Heorot by Larry Niven, Jerry Pournelle and Steven Barnes; maps by Alexis Walser". Los Angeles Times . Retrieved 13 January 2021.

References [edit]

- Chaney, William A. 1999 [1970]. The Cult of Kingship in Anglo-Saxon England: The Transition from Paganism to Christianity. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0719003725

- Fulk, R.D.; Bjork, E. Robert; & Niles, John D. 2008. Klaeber'south Beowulf. Fourth edition. Academy of Toronto Press. ISBN 9780802095671

Who Is Herot In Beowulf,

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heorot

Posted by: banksobling.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Who Is Herot In Beowulf"

Post a Comment